Guest article provided by: kpsychology.com

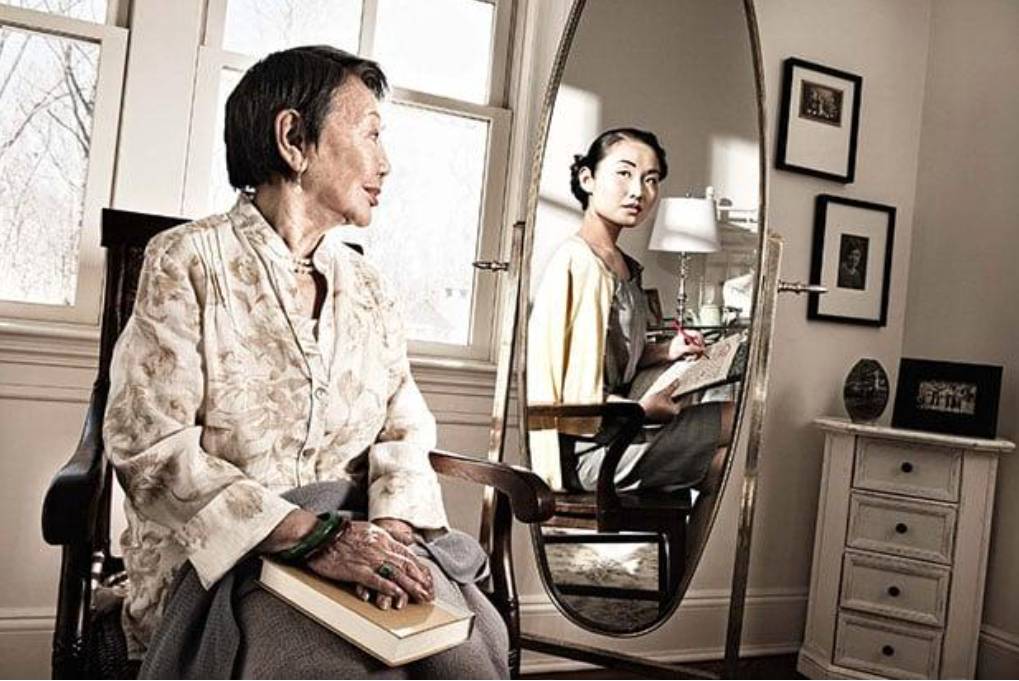

The process of aging is complex and influenced by multiple factors, impacting the human body at various levels and leading to both biological and psychological transformations. Research consistently highlights the profound impact of subjective age on mental and physical health, cognitive functions, and overall well-being.

Psychology of Aging

Numerous studies have identified various subjective psychological concepts to explore psychological aging, encompassing elements such as subjective age, age identity, the aging self, attitudes toward one’s own aging, self-perceptions of aging, and satisfaction with aging.

Several research studies indicate that adults commonly experience a tendency to perceive themselves as younger than their actual age, and this difference tends to grow with advancing calendar age (1,2). For example, even those older than 25 usually see themselves as younger than they really are (3).

A review of 19 long-term studies revealed that how people feel about their age has a small yet meaningful impact on their health, health habits, and how long they live (4). Stephan and his team found a link between feeling older than one’s actual age and increased inflammation in the body and higher chances of obesity (5). Additionally, thinking of oneself as older was connected to specific health issues, such as diabetes (6).

Subjective Age and Depression

Keys and Westerhof (7) found a connection between how individuals see their own aging process, their actual age, and their mental well-being. They found that feeling younger than one’s age is linked to better mental health, a lower risk of depression, and an overall mental health well-being. Interestingly, wanting to be younger had no connection to depression and overall mental health well-being.

In a study over time conducted by Choi and Dinitto (8), perceiving oneself as older predicted more depressive symptoms in the future. However, feeling younger did not lead to a decrease in depressive symptoms in a subsequent study. Moreover, a long-term investigation into depression and chronic illness revealed that seeing oneself as older than actual age might be a risk factor for future physical health issues and depression (9). This suggests that our mental state can influence our overall health.

Subjective Age and Cognition

Feeling younger than one’s actual age is linked to enhanced memory function. Stephan and his team demonstrated that having a sense of younger age correlated with better cognitive performance a decade later (10). Beyond the impact of chronological age, perceiving oneself as older was associated with an increased risk of dementia in individuals aged over 65 over a four-year span. Interestingly, the researchers highlighted that this connection was influenced by symptoms of depression (11).

Subjective Age and Mortality

Stephan and colleagues established a link between subjective age and mortality risk across three sizable samples (12). On average, participants reported a subjective age 15% to 16% lower than their actual age. Notably, having a subjective age 8-13 years older was associated with an 18-29% higher likelihood of mortality, respectively.

A subsequent meta-analysis confirmed these findings, highlighting that chronic diseases, a sedentary lifestyle, and cognitive issues, but not depressive symptoms, played a role in the connection between subjective age and mortality. The study concluded that maintaining an older subjective age is correlated with an increased risk of mortality in adults. Additionally, age identity was found to predict overall and cardiovascular mortality over an eight-year period.

Subjective Age and Well-being

Research in this area suggests that people who feel psychologically younger than their chronological age are more satisfied with their lives than those who are psychologically older.

There are many factors that influence psychological age and how it is related to subjective well-being. Certain factors, known as non-modifiable factors, are challenging to alter through behavioral changes or therapeutic interventions. Non-modifiable factors encompass elements such as genetic predisposition, parental age, family members’ age at death, the age of one’s children, retirement age, and the average life expectancy in a given country.

Nonetheless, numerous factors are within our capacity to modify, aiming to decrease psychological age. These modifiable factors comprise health status and disabilities, levels of physical activity, expectations of longevity, educational attainment, biomedical knowledge, occupational engagement, environmental conditions, psychological support, social relationships, and personal beliefs. The influence of these factors on psychological age can, in turn, have a substantial impact on overall life satisfaction.

Strategies for Healthy Aging

- Cultivate a Younger Mindset:

- Foster a positive perception of subjective age.

- Embrace a mindset that aligns with feeling younger than your chronological age.

- Prioritize Mental Health:

- Acknowledge the link between subjective age and mental well-being.

- Engage in activities that promote better mental health and lower the risk of depression.

- Maintain Physical Health:

- Recognize the impact of subjective age on physical health.

- Adopt a healthy lifestyle, including regular physical activity, to reduce inflammation and lower the risk of obesity.

- Manage Chronic Diseases:

- Understand the connection between chronic diseases and subjective age.

- Proactively manage chronic conditions to mitigate their impact on aging perceptions.

- Enhance Cognitive Function:

- Recognize the association between feeling younger and improved cognitive function.

- Engage in activities that support cognitive health, such as mental exercises and lifelong learning.

- Promote Longevity Expectations:

- Acknowledge the role of expectations in subjective age.

- Cultivate positive expectations for a longer and healthier life.

- Keep Learning:

- Recognize the influence of education on psychological age.

- Pursue ongoing learning and educational opportunities to promote a youthful mindset.

- Occupational Engagement:

- Consider the impact of work on subjective age.

- Engage in fulfilling and meaningful work or activities to positively influence perceptions of age.

- Create Supportive Environments:

- Recognize the role of environmental factors in psychological aging.

- Foster environments that support well-being, positivity, and a sense of youthfulness.

- Nurture Social Relationships:

- Acknowledge the importance of social connections in influencing subjective age.

- Cultivate strong social relationships and connections to positively impact overall satisfaction with life.

- Address Non-Modifiable Factors:

- Recognize factors beyond personal control.

- Focus on aspects that can be modified to counterbalance the impact of non-modifiable factors on psychological age.

- Personal Beliefs and Attitudes:

- Understand the influence of personal beliefs on subjective age.

- Cultivate positive beliefs and attitudes towards aging to shape a more satisfying life experience.

By integrating these strategies into one’s lifestyle, individuals can actively contribute to healthy aging, promoting a positive subjective age and enhancing overall well-being.

References:

- Goldsmith RE, Heiens RA. Subjective age: a test of five hypotheses. Gerontologist. 1992; 32:312–17.

- Montepare JM, Lachman ME. “you’re only as old as you feel”: self-perceptions of age, fears of aging, and life satisfaction from adolescence to old age. Psychol Aging. 1989; 4:73–78.

- Rubin DC, Berntsen D. People over forty feel 20% younger than their age: subjective age across the lifespan. Psych Bull Rev. 2006; 13:776–80.

- Westerhof GJ, Wurm S. Longitudinal research on subjective aging, health, and longevity: Current evidence and new directions for research. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2015; 35:145–65.

- Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Terracciano A. Subjective age and adiposity: evidence from five samples. International J of Obesity. 2019; 4:938–41.

- Demakakos P, Gjonca E, Nazroo J. Age identity, age perceptions, and health: evidence from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007; 1114:279–87.

- Keyes CL, Westerhof GJ. Chronological and subjective age differences in flourishing mental health and major depressive episode. Aging Ment Health. 2012; 16:67–74.

- Choi NG, DiNitto DM. Felt age and cognitive-affective depressive symptoms in late life. Aging Ment Health. 2014; 18:833–37.

- Segel-Karpas D, Palgi Y, Shrira A. The reciprocal relationship between depression and physical morbidity: the role of subjective age. Health Psychol. 2017; 36:848–51.

- Stephan Y, Caudroit J, Jaconelli A, Terracciano A. Subjective age and cognitive functioning: a 10-year prospective study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014; 22:1180–87.

- Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Terracciano A. Subjective age and risk of incident dementia: evidence from the national health and aging trends survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2018; 100:1–4.

- Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Terracciano A. Subjective age and mortality in three longitudinal samples. Psychosom Med. 2018; 80:659–64.

Image by: Tom Hussey